Jewish Lens Mini Course

Lesson 3: Jewish Peoplehood

| Overview: | Jewish Peoplehood connects Jews to other Jews around the world, today and throughout history. Jewish peoplehood is an informed and active sense of belonging to the Jewish People based on common denominators.

In this lesson, students consider the meaning of “Jewish Peoplehood,” and begin to articulate their own personal connection to the Jewish People through discussion. |

| Schedule: | 1-2 Class Sessions

Introduction (15-20 minutes) What is Jewish Peoplehood (15-25 minutes) Photo Mission (15-30 Minutes) Share Photographs (10-20 Minutes) Wrap Up (5 Minutes) |

| Materials: |

|

| Preparation: | Set up projector to display the photographs. If laptop and projector are not available, make high-resolution photocopies of the photographs to distribute to students or place around the classroom. |

| Goals: |

|

Introduction (15-20 minutes)

Show the students the following images by Zion Ozeri:

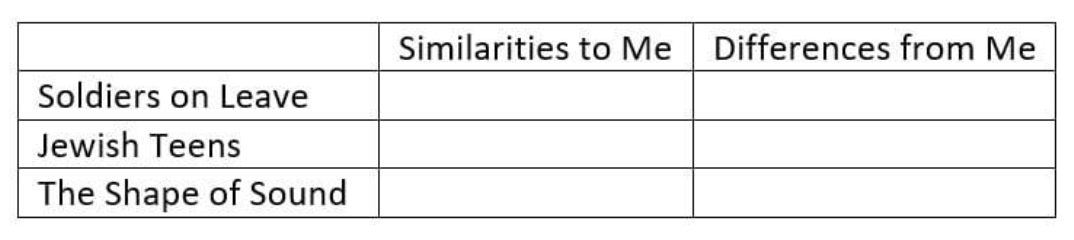

- Soldier On Leave, Israel – 2001

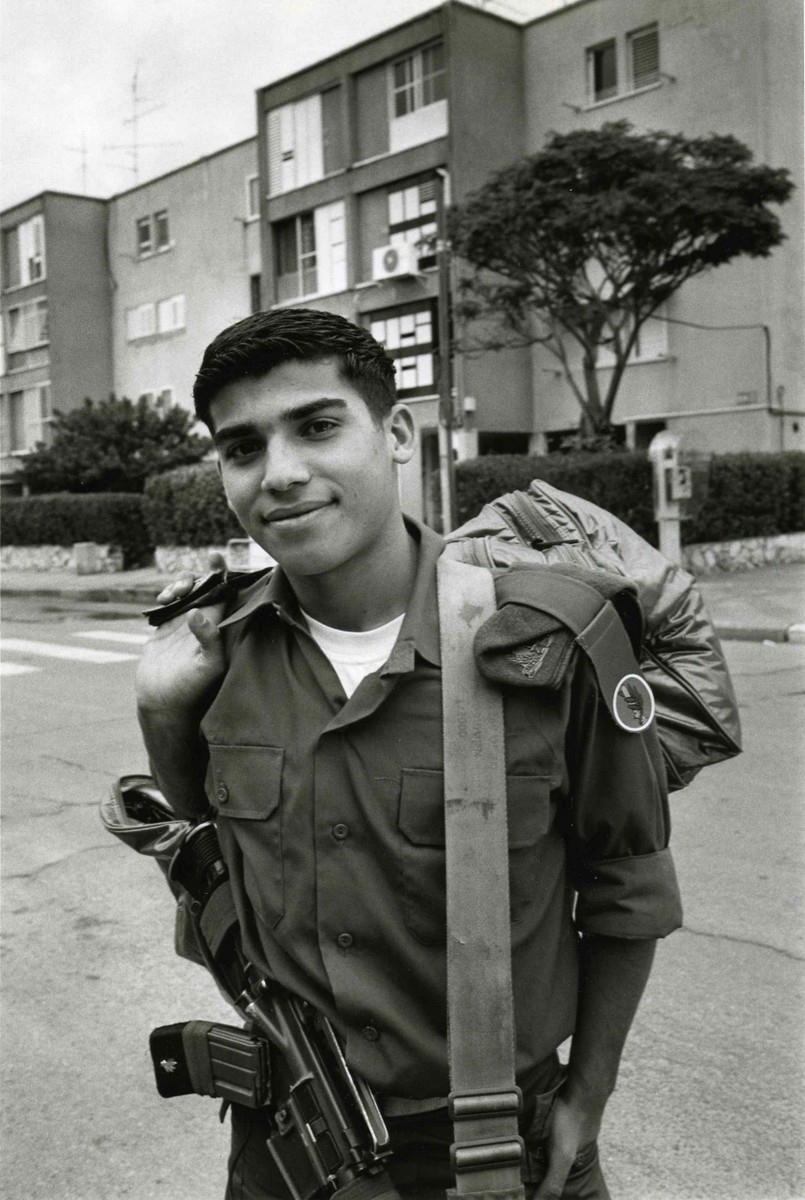

- Jewish Teens from Northern Westchester, New Orleans – 2006

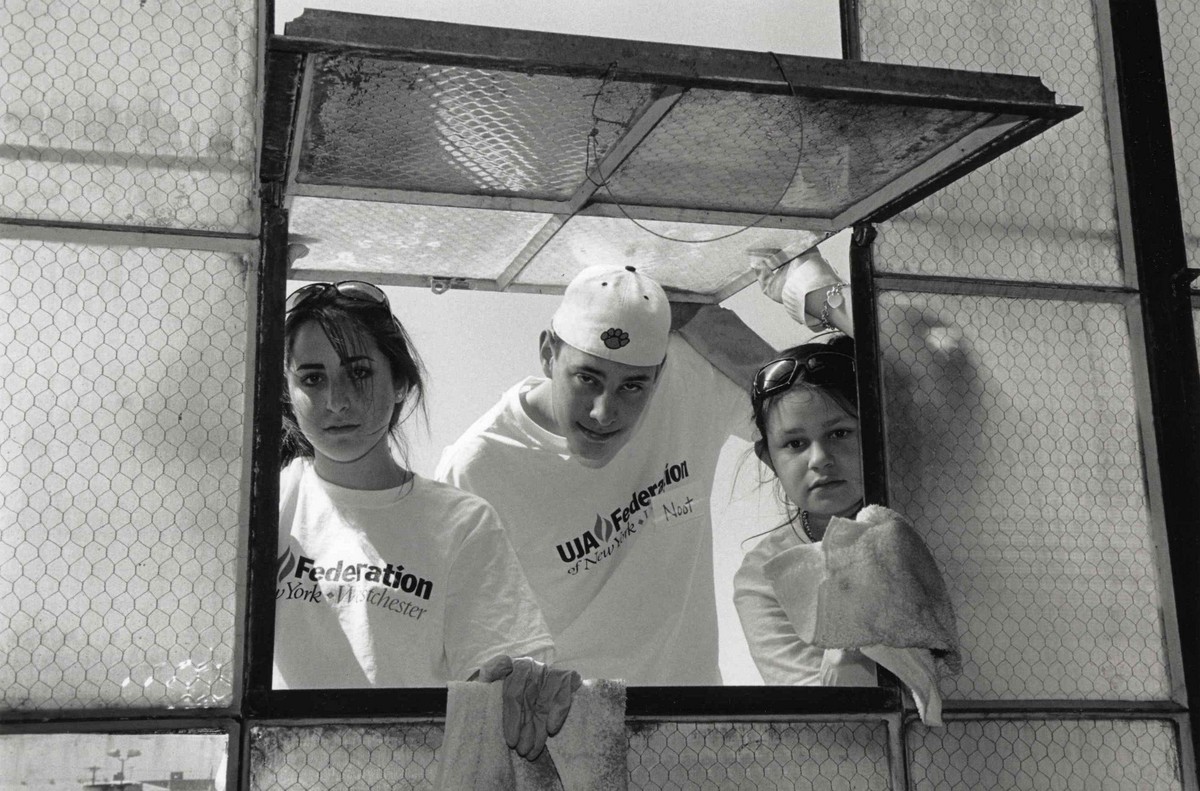

- The Shape of Sound, Yemen – 1991

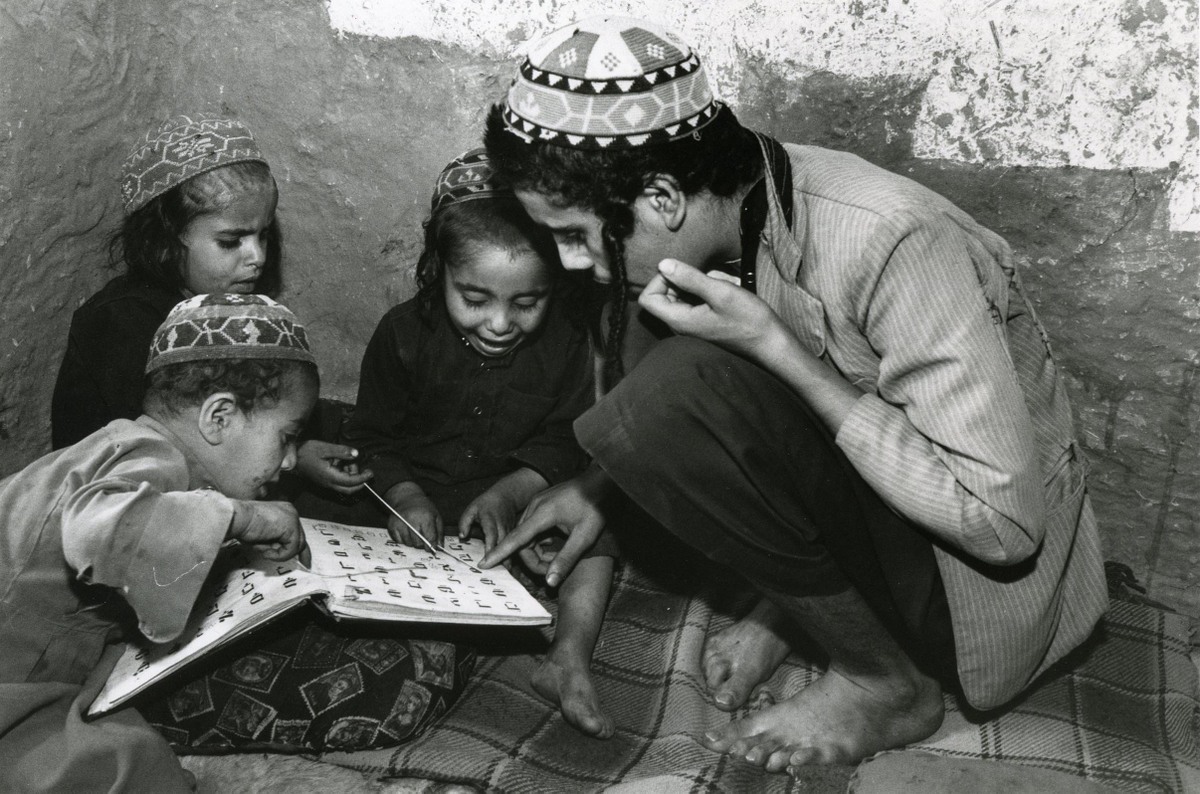

On the board, make two columns and label them: “Similarities” and “Differences.” Split these two columns into three, one for each of the photographs. One by one, display the images and ask students to identify all the differences they see (or can reasonably assume to be present) between themselves and the subjects of the photograph. Note their answers in the appropriate column. Then have students list the similarities.

Example:

Ask students:

- Do you think you’re more similar to or different from the people in this photograph?

- What makes these photos Jewish?

- Do you feel any connection to these people? Why or why not?

- What does it mean to you that you and they are both part of the Jewish people?

What is Jewish Peoplehood? (15-25 minutes)

You can write these on the board as you introduce each one, discussing the meaning of the pillar with the class. Ask the students to give examples for each (some suggestions have been given below). It is important here that students draw from their own knowledge and experience, so they relate personally to each of the pillars.

Historical memory

(A shared collective memory; re-telling our stories, for example at Passover)

Our understanding of a shared past that, to varying extents, continues to inform our lives. We express our pain and our joy using the communal language given to us by our history. These emotional experiences can take place whether we are celebrating the Exodus from Egypt, lighting the Chanukkah candles, commemorating the Holocaust, or otherwise marking Jewish events and experiences throughout the calendar year. Our history connects us with one another, and we pass these memories down to our children.

A Jewish Way of Life

(What is a Jewish way of life? Faith and lifestyle; rituals and traditions)

This concept refers to what Jews do in their homes and in their personal and communal lives as part of living a Jewish life. This could include lighting candles on Shabbat, fasting on Yom Kippur, celebrating a bar or bat mitzvah, building a Sukkah, and honoring Jewish customs. These practices, however they are undertaken, represent the desire to connect with something beyond one’s individual experience.

Jewish Values

(For example, Tikkun Olam)

Scholars debate whether or not it is possible to refer to particular values as being specifically “Jewish.” Some say that the values that we might attribute to a specific religion are actually universal values that each religion relates to in its own way. Others assert that there are, in fact, concepts that stem from a particular religion that were eventually embraced by the wider world. While the purpose of this article is not to weigh in on this debate one way or another, it is still important to acknowledge the character traits, ethics, and ideals that form the cornerstone of Jewish values; these values are not necessarily exclusively Jewish, but are nonetheless foundational ideals within Judaism. Typically, these terms are expressed in Hebrew, and include—but are not limited to—tikkun olam (repairing the world), tzedakah (justice/charitable giving), Talmud Torah (teaching and learning Torah), bikkur cholim(visiting the sick), hachnasat orchim (welcoming the stranger), and gemilut chassadim (acts of lovingkindness). Judaism has an ethical and moral language that, however it is expressed, is, by necessity, a fundamental and inseparable part of an individual or community’s Jewish life.

A Multifaceted Connection to Israel

(Have any of the students visited before? How often? Do they feel a connection to the land? What does Israel mean to them?)

The Land of Israel, Zion, the Jewish Homeland: these are just a few ways of articulating an idea that has always been a major part of Jewish history and Jewish spirituality. From the very beginning of the Bible through the present day, Jews have related to this concept in a number of different ways, whether through religious texts, prayer, visiting the land, supporting the people and institutions in it, immigrating, or even by protesting against it. Some connect with the concept of Eretz Yisrael, the Biblical land that was promised to Abraham and which the Israelites reached after 40 years of wandering in the desert. Others think of it as a homeland, the culmination of the Zionist movement, and a necessary shelter in the wake of the Holocaust. Another perspective finds connection with the modern State of Israel, a country with nearly nine million people of different races, religions, and ethnicities: a highly successful nation, but one that has yet to reach an agreement with its neighbors and finalize its borders. Each of these approaches can be significant and meaningful ways to relate to a (physical or philosophical) place that looms large in the Jewish imagination.

Hebrew and Jewish languages

(Ladino, Yiddish, the importance in Jewish life placed on learning Hebrew from a young age)

Hebrew has been the universal Jewish language for centuries, regardless of any individual’s fluency in, and understanding of, the language. Nonetheless, it is not the only Jewish language. Yiddish, Ladino, and Judeo-Arabic are particularly prominent and important, though Jews around the world speak—and spoke—a myriad of different languages. Reading, speaking, and writing in one or more of these languages can be a powerful way to connect to people and subcultures within the Jewish community (Yiddishists, socialists, secularists, Zionists, Chassidim, to name a few), and Jewish history.

Jewish Culture and Creativity

(Do the students know of any examples of Jewish art, music, literature? Zion Ozeri’s photographs and the Jewish Lens photography competition are also examples of Jewish creativity)

The world of Jewish art and culture is vast, and there are a number of ways to make it a meaningful part of a Jewish life. The gateway itself is broad, and can refer to works by Jewish creators, Jewish creations, and Jewish interpretations of the works of others. In practice, this can include reading Jewish authors and poets, learning new piyyutim (liturgical poetry), attending an Israeli film festival, singing a new version of Adon Olam, or trying out a new recipe for Passover cake. Taking inspiration from a Jewish figure, such as photographer Anton Mislawsky, Maimonides, Regina Jonas, or Albert Einstein, can be a way of not simply learning from creative Jewish figures, but of reinforcing and reinventing that creativity. Similarly, challenging established thinking—in math, science, architecture, or any other field—is a proud and longstanding part of our tradition of questioning authority and thinking about the world in new and creative ways.

Explain that one might feel connected to one, a few, all, or even none of these pillars – each of our identities is layered, complex, and different from every other. Every individual has a unique way of defining what it means to be Jewish.

Hand out the Six Pillars of Jewish Peoplehood Photo Worksheet to the class and ask students to match each photo with one or more of the pillars (which will be displayed on the board) that they feel are connected or relevant. This task can be done individually or in pairs.

Once the students have made their choices, ask some of the students/pairs to briefly explain why they chose the pairings they did.

Alternatively, you can print and hang the images around the room. Ask students to move around the room and look at all the photographs and then to stand next to one they feel best reflects themselves, or their connection to Jewish Peoplehood.

Once everyone has chosen a photograph, ask several of the students to explain to the rest of the class why they chose that image. What is the message of the photograph? What about the photograph says “Jewish Peoplehood” to you?

Photo Mission (15-30 minutes)

Ask the students to think about which of the pillars they relate to most and then take a photograph (in the building, hallway, outdoors, etc.) that reflects the concept of that pillar. They can choose to take a photograph that reflects one pillar, or to take six photographs for all six pillars.

Make sure to review with the students the various compositional aspects introduced in Lessons One and Two before they begin.

Share Photographs (10-20 minutes)

Have the students share their photographs. Potential points for discussion:

- What did you take a photograph of and why?

- Which pillar did you choose and why?

- Were some of the pillars harder to represent than others?

- What compositional aspects did you consider?

- How would you improve the image if you could?

Wrap- Up (5 minutes)

Show the class ANU – Museum of the Jewish People’s video “You are Part of the Story”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O8_8z2quiBs

After the video, explain how the skills practiced in today’s lesson were preparation for the final assignment, in which students will be asked to connect their art/photography to their personal Jewish story.

IMAGES

Soldier on Leave, Or Akiva, Israel, 2001

This young Israeli soldier is a member of the Kavkazi community, Jews from the Caucasus Mountains of southern Russia and Azerbaijan. The origins of the Kavkazi community are mysterious—some believe their story began more than 2,500 years ago with the Jewish exile to Babylon. But throughout their history, the Kavkazi Jews always longed to return to Eretz Yisrael. In recent decades, their dream has become reality; there are more than 100,000 Kavkazi Jews living in Israel today.

Like young Israelis of all backgrounds, most Kavkazi youths enter the army at age 18. Men usually serve for three years; women for two. Typically, men are also called up for reserve duty every year until about age 40.

Sample Texts:

For instruction shall come forth from Zion, the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. Thus He will judge among the nations and arbitrate for the many peoples, and they shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks: Nation shall not take up sword against nation; they shall never again know war.

– Isaiah (Yeshayahu) 2:3-4

It is true we have won all our wars, but we have paid for them. We don’t want victories anymore.

– Golda Meir

Jewish Teens from Northern Westchester UJA Federation, New Orleans, LA, 2006

These young people have traveled from Westchester County, New York, to New Orleans, Louisiana, to volunteer in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina. In the photo you can see them cleaning a building that was damaged by the floods. Many members of the world Jewish community donated their money and time to help those affected by the disaster. Adam Bronstone, of the New Orleans Jewish Federation, commented on the contributions of such volunteers: “They can’t fix levees. They can’t put people in FEMA trailers. But they can help brighten up someone’s day. Things are pretty dark now, and volunteers of all ages are continuing to give to this city” (New York Jewish Week, February 24, 2006).

Sample Texts:

It is to share your bread with the hungry, and to take the wretched poor into your home; when you see the naked, to clothe him, and not to ignore your own kin.

-Isaiah (Yeshayahu) 58:7

We support Jewish and non-Jewish poor; we visit Jewish and non-Jewish sick and bury Jewish and non-Jewish dead, to promote the ways of peace.

– Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 61a

Do not be wise in words – be wise in deeds.

– Yiddish saying

Shun evil and do good,

Seek peace and pursue it.

– Psalms (Tehilim) 34:15

The Shape of Sound, Yemen, 1991

Whether you’re in a cave in Yemen or a yeshiva in Brooklyn, the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the words of the Torah remain the same. It is these universal Jewish traditions that keep communities connected across time and space.

Why do you think the photographer calls this picture The Shape of Sound?

Sample Texts:

Ben Zoma said: Who is wise? One who learns from all people, as it is written (Psalm 119:99) “I have gained understanding from all my teachers.”

– Pirkei Avot 4:1

Rabbi Chalafta of Kefar Chanania used to say: If ten people sit together and occupy themselves with the Torah, the Divine Presence rests among them as it is written (Psalm 82:1) “God has taken his place in the divine assembly.” And from where do we learn that this applies even to five? Because it is written (Amos 9:6) “He has established his vault upon the earth.” And how do we learn that this applies even to three? Because it is written (Psalm 82:1) “He judges in the midst of the judges.” And from where can it be shown that the same applies even to two? Because it is written (Malachi 3:16) “Then those who revered the Lord spoke with one another. The Lord took note and listened.” And from where even of one? Because it is written (Exodus 20:24) “In every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you.”

– Pirkei Avot 3:7